Censorship is a touchy subject, and rightly so. No one wants to wake up and discover that they are living in 1984, and that they’ve committed seventeen thought crimes before breakfast. No one wants to wake up and find that the firemen have come to burn your books. No one – well, maybe recent events suggest that there are those who would like to move in one totalitarian direction or another, that they would quite like to give up free thought and just do what they are told.

I don’t know about you, but for me a mix of books is essential in order for different ideas to collide, for inspiration to spark when two concepts get short circuited by adjacent neurons in my brain. The best ideas come from the bringing together of widely different precursors, like the BFG mixing dreams. On that basis, reading different kinds of books is crucial.

But is there ever a case for banning a book? Anne Fadiman mentions in one of her essays that her father turned a book around on the shelf because he didn’t want her reading it – which of course gave the book added glamour and allure. Parental censorship has a time-bound quality to it: once you are of age, if you still have the will you can look up anything that your parents stopped you from reading when you were younger. And of course, teenage rebellion will see to it that a ban is defied. This is writ large when the State assumes that parental authority and decides that it is in the public interest for a book to be banned.

Some people have played the system: James Branch Cabell’s sales went up dramatically when he was taken to court on obscenity charges by the League for the Suppression of Vice. On the other hand, Banned Books Week is an international effort to raise attention to the practice of censorship that is going on around the world at this time.

But I return to the question, is it ever justifiable to ban a book? Last year I read the amazing ‘Fall of the Gas-Lit Empire’ trilogy, by Rod Duncan (which, incidentally, I cannot recommend highly enough). At the heart of the story is the International Patent Office, which is suppressing knowledge and stifling invention, for reasons that only really become clear towards the end of the trilogy. One of the things that can be said as a criticism of this suppression is that it leaves social change almost completely stagnant. Imagine if, living today, women didn’t have the vote, indentured service was still a very real possibility for those not paying their debts, and anyone who doesn’t conform with the societal norms of two to three hundred years ago is a pariah at best. But a justification can be made.

As a younger man, I would have said that there was never a reason to ban a book, but now older, and more appreciative of nuance, I begin to wonder if there can be a case for banning a book. This new view is perhaps informed by the changes that we have seen in how experts are viewed. Back in 2016, Michael Gove declared that the public had had enough of experts, in part because no economist would back his view of Brexit. It’s the kind of meme-worthy idea that has taken root, but it is not always clear when it is being used ironically.

I’ve seen a couple of books recently that have the potential to be quite harmful. The worst part is that they come from people who are positioning themselves as experts, but have no authority for these expertise (except the ‘University of Life’) and provide no literature for the support of their views. I feel that there is a case to be made for banning them – but perhaps the better stance is to ignore them, to promote the good books.

What’s your view? Is censorship ever justifiable? Who gets to decide? Are there any books you would ban?

© David Jesson, 2020

This is a real and sticky problem for librarians (amongst others) through the ages, although sometimes the problems take on a new nuance. A real life example justifying a limited control of books came when I was studying for my professional qualification.* A guest lecturer, a reference librarian, asked if it was professional and responsible to give a 12-year old a reference book about explosives? Obviously not, but that has been wholly negated by the irresponsible promulgation of information (and pornography) on the internet.

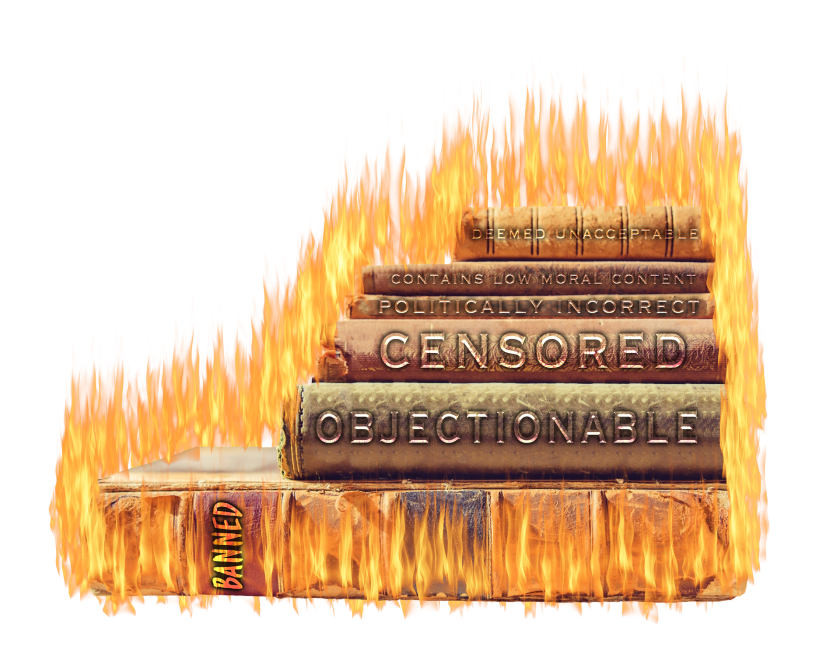

So yes, there is a case for controlling supply of books which depending on which side of the argument you stand, may or may not be censorship. I do not, most emphatically, agree with the wholesale burning of books, not he method of censorship shown in ‘The Name of the Rose’. 🙂

*This was back in the Dark Ages of 1967! 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

I believe in what Voltaire said: “I do not agree with a word you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” However, banning a book is not the same as boycotting a book or boycotting an author. People have the right to say what they want, and other people have the right to refuse to listen.

LikeLiked by 2 people

One of my favourite sentiments – although I hear that Voltaire may be coming under the scrutiny of cancel culture. That’s a very neat, thoughtful way of putting the point though, James – I don’t suppose it would catch on, but I wonder if there should be a ‘boycott’ option on review sites.

LikeLiked by 2 people

So I just read up on why people want to cancel Voltaire. I was not aware of his antisemitic and pro-slavery views. That’s disappointing. Given the era he lived in, though, I’m not too surprised. He may not live up to our standards today, but I still think he was still ahead of his own times.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yep. I think the sentiment still stands, but we have to be ready to apply it in situations that Voltaire wouldn’t have considered, either because they didn’t exist when he lived, or because of his prejudices.

LikeLiked by 1 person